The times were fraught with uncertainty for settlers on the western frontier of the original thirteen American colonies prior to the Revolutionary War. In particular, the edge of “civilization” as they knew it landed at the slopes of the Appalachian Mountains in the western regions of Virginia and North Carolina. The risks were high, although they lived under the rule and protection of the British Crown in the form of a colonial government. Treaties had been forged with the Cherokee, Chickamauga, and Shawnee tribes, but tensions remained high between those who did not offer nor appreciate a compromise. Since settlers were separated from the hubs of legislative participation by a mountain range and weeks of travel, the inhabitants of those frontier settlements began to govern themselves. Ultimately, they decided it was a good idea to declare themselves autonomous, secede from North Carolina, and to call their new state…Frankland?

Franklin, not Frankland

Technically, it all began when William Bean decided to settle in what he thought (or hoped) was a region belonging to Virginia in 1769. He built a cabin along the banks of the Watauga River and began to carve out an existence in this region just beyond the Appalachian Mountain range. He was soon joined by other settlers from Virginia, creating a small community next to this beautiful river, and other nearby river tributaries.

However, when the area was surveyed by John Donelson in 1771, it was discovered that the settlement was not located in Virginia, but it was actually beyond the legal border of the colonies and west of North Carolina, as determined by the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This did not deter the group from continuing to grow and attract other settlers, though their activities were considered illegal by the British Crown. The settlers had several local indigenous tribes as neighbors with whom they generally had an amicable trade partnership, but there were other tribes that justifiably took their presence as an encroachment and a threat since they were beyond the colonial borders.

By 1772, the settler community had grown so large that they needed a means to organize themselves into some sort of government. They were literally outside the jurisdiction of the colonial government, so they really had no choice but to take on the responsibility for their own community. This first foray into an independent “self-rule” was called the Watauga Association. The settlement was centered along the Watauga River in what is now Elizabethton, Tennessee. The founders of this association relied upon peace with the local Cherokee tribe as a condition of a 10-year lease they had negotiated for themselves. The founders cooperated with the local Cherokee tribal leader, Attakullakulla. However, this too was considered an illegal act.

The Wataugans first elected five magistrates to uphold the laws as defined by the “Articles of the Watauga Association,” which are believed to be based upon Virginia law of the day. They would oversee the construction of a courthouse and a jail, they managed record-keeping for deeds and wills, and they would also manage the protection of the settlement, which became more and more pressing as time went on. Although there is no known copy of the Articles, nor any records, it is clear that the Wataugans still considered themselves to be British subjects and subject to colonial rule. The Watauga Association was merely a solution to being without direct access to government assistance or involvement, although their independent arrangement seemed to set a dangerous precedent to some in colonial leadership, namely the Virginia governor, Lord Dunmore.

The growing unrest with their indigenous neighbors, who were not all from the same tribe, nor bound by the agreements made by Attakullakulla, became an issue. Case in point, when the Wataugan settlers negotiated the purchase of their leased land in 1775, Chickamauga, Shawnee, and more distant Cherokee tribes took great umbrage with the land deal. Attakullakulla’s son, Tsiyu Gansini (commonly known as Dragging Canoe), refused to remain peaceful regarding his father’s agreement. This stance would eventually lead to the long and bloody 18-year Cherokee War, which began in the summer of 1776. Battles between the white settlers and the Cherokees, led by Dragging Canoe, who said that the colonists had “surrounded us, leaving only a little spot of ground to stand upon, and it seems to be their intention to destroy us as a Nation.” Dragging Canoe refused to relent over the war years and proved to be a formidable opponent and military mastermind. So much so that some of the white settlers referred to him as “The Dragon,” and some modern-day historians now refer to him as “The Red Napoleon.”

Additionally, in 1775, everything would shift when the Revolutionary War began. The Watauga Association officially renamed itself as the “Washington District,” and established a Committee of Safety, signaling their alignment with the united colonies. They also began construction of Fort Caswell (more commonly known as Fort Watauga) in 1775, foreseeing a need to defend themselves from British aggression.

In the spring of 1776, the Washington District issued a formal request to be annexed by Virginia, but Virginia denied the request. A similar letter of request was sent to North Carolina in July of 1776. North Carolina did accept the annexation request, and the Washington District representatives were allowed to attend the Provincial Congress in Halifax, North Carolina during the November-December 1776 session. In November 1777, the region west of the mountains all the way to the Mississippi River was annexed by North Carolina, and the name “Washington District” was applied to the whole area.

After the war, several of the Committee members returned to the Washington District and continued to serve as elected representatives for the region in the North Carolina Congress although some were more focused on continued and extensive battles with the indigenous population in what was eventually called the Cherokee-American Wars. At the same time, the Continental Congress was pushing the colonies to cede their vast western counties to pay for the debt accrued during the Revolutionary War. North Carolina agreed to do so in April 1784, issuing a cession for all of their territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. This left all of the inhabitants of the western region with the very real fear that the land would be sold out from beneath their feet, as well as leaving them with zero governance.

In response, the settlers living in the original Watauga Association, also known as the Washington District, began to organize themselves, as they had already done twice before. This time, their intent was the creation of a new, 14th state that would encompass the same area they had maintained jurisdiction over since 1772. They already had an infrastructure of their own creation and could readily continue to build upon it. The solution to “do it themselves” seemed to be the most logical response to North Carolina ceding their land.

On 23 August 1784, the state of “Franklin” was established by a meeting of regional delegates in Jonesborough (near Elizabethton) led by Arthur Campbell of southwestern Virginia. The vote to form a new state was unanimous and the delegates were scheduled to reconvene in December to vote on a constitution. Campbell wanted to propose a very large area of land to become a new state, including various parts of surrounding colonies. He wanted to call his concept “Frankland.” The original area of the smaller Washington District, comprising just eight counties, was called “Franklin,” and this was supported by John Sevier, a former Committee of Safety member. It seems these names were used rather interchangeably, and the proposed state boundaries remained nebulous.

In November 1784, the North Carolina legislature decided to not cede the Washington District, perhaps realizing the power vacuum that would then exist in the region without active governmental management. This fact was essentially ignored by Franklinites, and they forged ahead with their plans to adopt a state constitution and to submit a petition for statehood. The first governor was John Sevier, who accepted the title rather reluctantly. In May 1785, Sevier took a delegation to Congress to present the petition for statehood of Frankland for approval. The petition received 7 of 13 votes in approval, falling shorts from the 9 votes necessary to earn a 2/3 majority, as required.

Regardless of the statehood outcome, the Franklin government continued to operate with Greeneville as its capital, while North Carolina delegates operated from Jonesborough. Each pretended the other wasn’t there and had no authority. Ultimately, Franklin was a losing cause. Its barter-based economy could not compete with a monetary system. North Carolina had funding, a vast militia, and the authority to control land that was still legally theirs. The retaliation from the Cherokee who felt wronged by broken treaties was incessant, causing Franklin residents to gravitate to North Carolina authorities who had far more resources to protect them from attack. North Carolina also had the ability to waive taxes for two years—a popular policy no matter who you are.

Sevier did not want to let his state-maker dreams come to naught, however, and so ousting him became a dramatic undertaking that pitted him against his North Carolina counterparts to the point of having a military stand-off at the home of Col. John Tipton. In February 1788, Sevier arrived at Tipton’s farm in an attempt to gain back his seized property (supposedly seized by court order due to unpaid taxes). The “property” was slaves from his farm that were being held in Tipton’s “underground kitchen.” Over the course of two days, nearly 300 men faced each other with guns at the ready. Shots were fired, men were killed, others were captured, and it spelled out the beginning of the end of Franklin.

In February 1789, Sevier took an oath of allegiance to North Carolina and was pardoned by the governor. By November, he’d been reelected as a delegate from Greene County and participated in legislative activities as if Franklin was just a memory. It was a seamless transition from Franklin to North Carolina government, because Franklin just stopped, while North Carolina carried on with business as usual. Sevier’s political journey did not end there. He became a founding father of the State of Tennessee, serving as the first governor of the state after being elected in 1796. He would go on to serve a total of six two-year terms, with term limits prohibiting him from serving additional consecutive terms. Following the governorship, he served three terms in the United States House of Representatives, beginning in 1811. Only his death on 24 September 1815, at the age of 70, could put an end to his political career.

Weekly Discoveries

The newly available collection Texas, U.S., Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Antonio Sacramental Records, 1700-1995 may provide insight into the lives of ancestors who resided in either the State of Texas or the Republic of Texas.

Learn about Attaching Sources to FamilySearch Family Tree in this upcoming free webinar.

Cherokee Nation celebrating grand opening of National Research Center in Tahlequah.

Records of the Almost-Fourteen Colonies

The State of Franklin was one of four regions vying to become the self-governing fourteenth colony of the early United States - an honor which eventually went to Vermont as Vermonters rose in resistance to land grant disputes between the colonies of New Hampshire and New York. What were these other almost-colonies and what happened to the records created by the people who lived in them?

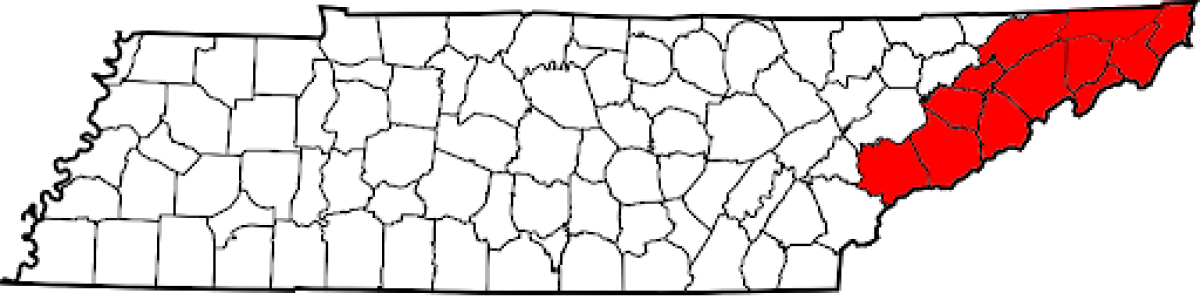

The State of Franklin comprised the twelve modern Tennessee counties of Blount, Carter, Cocke, Greene, Hamblen, Hawkins, Jefferson, Johnson, Sevier, Sullivan, Unicoi and Washington. Few county-level records from the Franklin era have survived to today, having been destroyed through several instances of records loss. Washington County is one of the only counties which has surviving records of the time period, including letters and estate records which have been digitized through their county archive website. Other records that do remain are scattered throughout various repositories in Tennessee, North Carolina and Virginia (particularly Fincastle County, which houses earlier records of many of the Franklin settlers).

Another region was formed by the Transylvania Company, a company headed by North Carolina land speculator Richard Henderson. The company purchased, from the Cherokee, a large tract of 20 million acres west of the Appalachian Mountains, in what is now most of central and eastern Kentucky and parts of northern middle Tennessee. The land had also been claimed by both the Virginia and North Carolina colonies; therefore, Henderson, in an effort to consolidate his claim, sent his agent Daniel Boone to find a path to that land through the Cumberland Gap and establish settlements. Boone set out from Fort Watauga in the State of Franklin and carved out what became known first as Boone’s trail, and then as the Wilderness Road – one of the two major migration trails into Kentucky. The Virginia colony disputed the purchase in what is now Kentucky and annexed the land, eventually nullifying the agreement altogether and claiming the land in the Transylvania Colony for itself. The North Carolina colony followed suit and invalidated the Tennessee portion of the claim, reclaiming that land for themselves. The Tennessee portion remained unsettled during the Transylvania Colony era, but the Cumberland Settlement was formed by Henderson shortly thereafter. When Virginia created Kentucky County, it was formed from Fincastle County, Virginia. Historical boundary maps, such as the Atlas of Historical County Boundaries from the Newberry Library shows how counties have been formed since then. Records regarding the Transylvania Colony can be found in various repositories in Kentucky, North Carolina and Virginia.

The third region was the Wyoming Valley Region of Pennsylvania (Scranton/Wilkes-Barre metropolitan area).The land was originally granted to the Connecticut colony by King Charles II of England in 1662, but when Connecticuters (or Yankees) began arriving to settle the valley over 100 years later in 1769, it was discovered that King Charles had also granted the land to the Pennsylvania colony in 1681, and settlements had already been established by Pennsylvanians (or Pennamites). The land dispute resulted in skirmishes now called the Pennamite-Yankee War (or, alternatively, the Yankee-Pennamite War). During the dispute a makeshift government was established for the region by Connecticut in what was to be a new state called Westmoreland. However, in 1775 the Pennsylvania militia invaded Westmoreland and claimed the land. The grant dispute was ongoing throughout the American Revolution and after the war the Continental Congress awarded the land to Pennsylvania. A compromise was reached with the Connecticut settlers whereby they would become citizens of Pennsylvania and have their properties restored. Records of the early Westmoreland settlers can be found at various repositories in Connecticut and Pennsylvania. Northampton County was the original county which covered the Wyoming Valley region from 1752-1772, ending in the mid-Westmoreland era, and records are available from 1752. Follow county formations in the Atlas of Historical County Boundaries to determine additional counties where records may be held.

Although these three states may have failed, their settlers went on to become the earlier colonial ancestors to many. If you can claim these settlers among your own, your research may now take you to new and interesting places and archives which will further enhance your family story. Happy searching!

——————

Documentation and citations are integral to organized, accurate and productive research. Learn more from our archive article Document! Document! Document!

Sources….Duh!!

James William Hagy, “Democracy Defeated: The Frankland Constitution of 1785,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, (Fall 1981), pp. 239–41; e-journal, (http://www.jstor.org/stable/42626207 : accessed 6 December 2021).

History.com (https://www.history.com : accessed 4 Dec 2021), “State of Franklin Declares Independence.”

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, (https://ncdcr.gov : accessed 6 December 2021), “The Lost State of Franklin.”

Tennessee Encyclopedia (https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net : accessed 6 December 2021), “State of Franklin,” rev. 6 Mar 2018.

TN Gen Web Project (https://www.tngenweb.org: accessed 7 December 2021), “East Tennessee Pre-1796: Petition of the Inhabitants of Washington District, Including the River Wataugah, Nonachuckie, etc., 1776.”

Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fort-watauga-sevier-sherrill-tn1.jpg : accessed 8 December 2021), digital image from illustration, 1903, “File:Fort-watauga-sevier-sherrill-tn1.jpg;” image uploaded by user BrineStans.

Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikime Der Bischof mit der E-Gitarredia.org/wiki/File:John_Sevier.jpg : accessed 4 December 2021), digital image painting by Charles Willson Peale, 2007, “John Sevier.jpg;” image uploaded by user Der Bischof mit der E-Gitarre.

Michael Toomey, Tennessee Encyclopedia (http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net : accessed 8 December 2021), “State of Franklin.”

FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org), "State of Franklin Genealogy," rev. 04:44, 5 June 2020.

Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Tennessee_highlighting_Former_State_of_Franklin.png : accessed 8 December 2021), digital image of user created map, 2006, “File:Map of Tennessee highlighting Former State of Franklin.png;” image uploaded by user Esemono.

Michael Toomey, Tennessee Encyclopedia (http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net : accessed 8 December 2021), “Transylvania Purchase."

Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wilderness_road_en.png : accessed 8 December 2021), digital image map, 2000, “File:Wilderness road en.png;” image uploaded by user Nikater.

FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org), "Kentucky County, Virginia Genealogy," rev. 12:40, 24 March 2021.

FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org), "Northampton County, Pennsylvania," rev. 14:56, 2 December 2021.

Encyclopedia Britannica (http://britannica.com : accessed 8 December 2021), “Pennamite-Yankee Wars.”

Judy Jacobson, History for Genealogists: Using Chronological Time Lines to Find and Understand Your Ancestors (Baltimore: Clearfield Company, 2016]), 7:117-120.

Albert Bender, Tennessean (https://www.tennessean.com/ : accessed 8 December 2021), “Dragging Canoe: A true American Indian hero.”